Heritage Minute showcases life-saving impact of U of T’s insulin discovery

(Photo by Alie Rutty)

After decades studying the 100-year-old discovery of insulin and its later development, Christopher Rutty faced a daunting task: select the most compelling details to be showcased in just 60 seconds.

A medical historian, he was one of three historical consultants on the team that created a new Heritage Minutes segment that pays tribute to the discovery of insulin at the University of Toronto’s department of physiology in 1921.

The segment follows the patient journey of a young and emaciated-looking Leonard Thompson, who would become the first diabetes patient to be successfully treated with the life-saving extract. Working away in their laboratory, scientists Frederick Banting and Charles Best offer an extract that they believe may save the child, who receives the treatment at Toronto General Hospital. In the evening, however, they receive a knock on the door from collaborators J.J.R. Macleod and James Collip, who says the extract is not pure enough.

“So, we try again,” Banting responds with defiance. “And again. And again.”

The decision to highlight the story of a single patient stemmed from a desire to emphasize the human element of the Nobel Prize-winning scientific discovery, according to Rutty, an adjunct professor at U of T’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health.

“If you’re going to reduce it down to a 60-second story, that’s a key moment,” Rutty says. “It shows the drama of the impact of insulin, which was that it practically resurrected the dead.”

A self-described stickler for details, Rutty says he felt a sense of responsibility to portray the story accurately because of the memory of his late PhD thesis adviser, U of T University Professor Emeritus Michael Bliss, who wrote the acclaimed book The Discovery of Insulin.

Rutty is also the lead historian for Defining Moments Canada’s Insulin 100 website, which features a series of articles authored by Rutty that recount the historical events leading up to and following insulin’s discovery – including the story of Thompson’s treatment.

He says he drew on Bliss’s work, original documents and newspaper reports from the period to help the Heritage Minutes team develop a full historical reconstruction of what took place. The short films are released by Historica Canada, a Toronto-based non-profit that seeks to generate awareness of Canadian history.

In a nod to Bliss’s conclusion that all four scientists in the team were critical to the discovery, Rutty felt it was important that Banting, Best, Macleod and Collip all be depicted and named.

“It was critical to make sure what the Heritage Minute was saying was true,” says Rutty. “Heritage Minutes are a record. They have a reputation of being well-done and historically responsible, and they are often an entry into the story for students and the general public.”

Alexandra Carter, science and medicine librarian at U of T’s Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, says she was struck by the historical accuracy of the visual details in the Heritage Minutes segment.

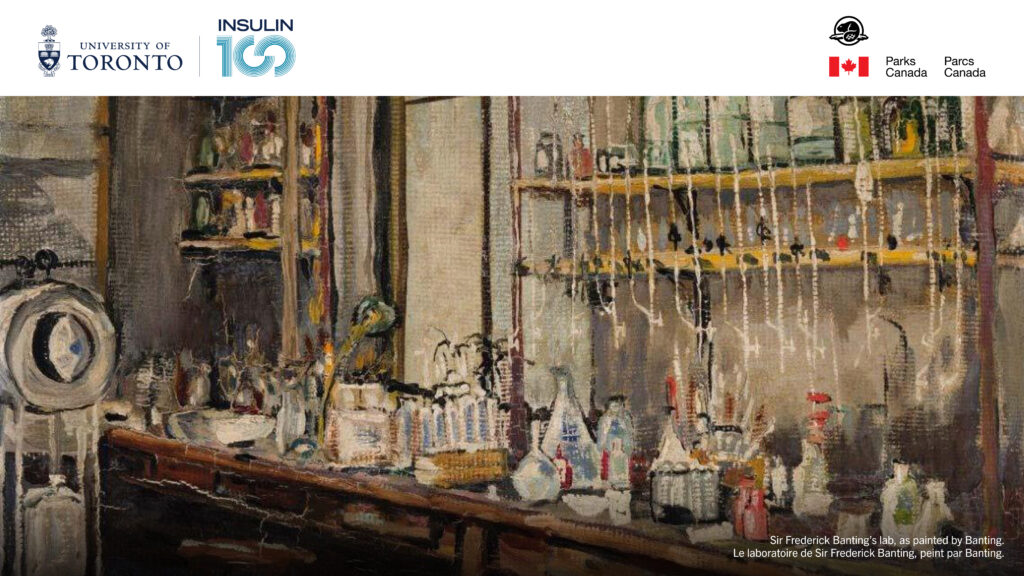

“We have photos of the lab; it’s this shoddy-looking, cluttered space where this amazing discovery took place,” Carter says. “I love that they put that in. I was also impressed by the attention to detail with Banting’s round glasses and their outfits – I could tell right away who was who.

“Banting was known to be a bit dramatic, so they got that right as well with the voiceover.”

Carter and Natalya Rattan, an archivist at the rare book library, have curated an online exhibition in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the breakthrough. Drawing from U of T’s extensive archives, as well as a 1996 article by Bliss, the exhibition chronicles the team’s tribulations and eventual triumph. The story is told through original handwritten notes and notebooks from the scientists themselves, patient charts, newspaper articles, letters and other historical documents.

The Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library also recently contributed to the creation of a new commemorative Canada Post stamp, which features the image of an excerpt from Banting’s unpublished memoir and an original insulin bottle with a red cap.

As for Thompson, there are few archival materials despite his reputation as the first patient to be treated with the extract, Rattan says.

Patient records from Toronto General Hospital indicate that he was 13 years old and weighed just 65 pounds. He received an injection of the first extract on Jan. 11, 1922, followed by the second version of the extract on Jan. 23. The latter shot proved dramatically successful, as Thompson’s blood sugar dropped to normal in one day.

The Heritage Minute ends with a close-up shot of Thompson, whose previously listless face blossoms into a smile as the insulin takes effect.

“When people come to see the records – they are often diabetics themselves, or doctors and pharmacists with direct connections to patients – they are always really drawn to the patient stories,” Rattan says.

“The patient narratives within the archives are at the heart of the discovery.”

Article by Yanan Wang