‘A molecular Swiss army knife’: U of T researchers uncover versatility of ancient DNA repair mechanism

If a bone breaks or a tendon snaps, you know to seek treatment immediately.

But your most fragile and precious cellular commodity, chromosomal DNA, breaks with astounding frequency – some estimate as many as 10,000 times a day per cell – usually without consequence.

That’s because legions of DNA repair proteins prevent genomic catastrophe by repairing DNA damaged by chemical or physical mutagens or just normal cellular wear and tear. Proteins dedicated to these tasks are common to all species. In fact, life as we (or bacteria) know it cannot exist without proteins that are dedicated to DNA repair.

Now, new research from Cheryl Arrowsmith, a professor in the University of Toronto’s department of medical biophysics in the Faculty of Medicine, reveals a previously unrecognized activity for one DNA repair factor that has been highly conserved through evolution.

“Our research revealed how a molecular Swiss army knife has multiple ways it can repair damage to our DNA,” says Arrowsmith, who is also chief scientist at the Structural Genomics Consortium (SGC) and senior scientist at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre.

“Our collaboration with colleagues in the U.S. provides a greater understanding of processes relevant to cancer and the function of immune cells.”

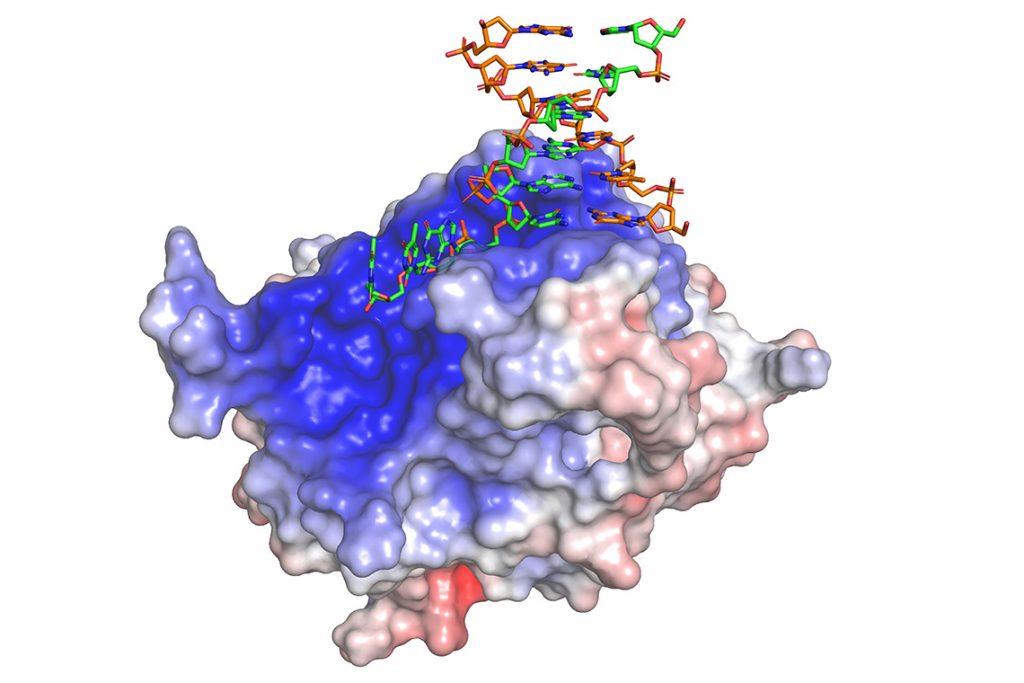

In a study published in July in the journal Nature Structure and Molecular Biology, Levon Halabelian, a research associate at the SGC, showed how the repair protein (known as HMCES and prounounced Hem’-sez) can recognize and trap several types of broken DNA strands.

Now in a second study published in Molecular Cell, Arrowsmith and collaborators including Anjana Rao at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology, and L. Aravind at the National Institutes of Health, show a new role for HMCES in which it helps a type of immune cell, called B lymphocytes, recombine their DNA to make certain classes of antibodies.

This finding means that HMCES, in addition to its role in repairing nicks in single DNA strands, also participates in what is called alternative end joining.

As the name suggests, alternative end joining is a secondary strategy used by mammalian cells to rejoin severe cuts across both strands of the DNA’s double helix. These and other recent reports suggest that a humble DNA repair factor whose history likely dates back several billion years performs multiple tasks to guard cells against genomic instability.

“When activated, normal B lymphocytes snip out a segment of their DNA that encodes antibodies called IgM and then reconnect the strand in order to make other more potent classes of antibodies,” says Vipul Shukla, the study’s first author, describing a DNA editing trick immunologists call class switch recombination (CSR).

“People have known for decades that immune cells use this kind of gene editing as a way to make potent antibodies. We found that HMCES not only recognizes these double strand breaks but helps reseal them.”

The Rao and Arrowsmith labs, which both study DNA-modifying epigenetic enzymes, became interested in HMCES because it had been reported to bind to DNA chemically modified by one such enzyme called TET.

Reasoning that HMCES and TET proteins might be engaged in similar biological tasks, the Rao lab genetically “knocked out” the HMCES gene in experimental mice, predicting that animals would display blood cell defects or even cancer – similar to outcomes caused by TET gene mutations. Surprisingly, that didn’t happen: The new paper by Shukla and the other researchers reports that blood cells from HMCES-deficient mice were normal and showed little disruption in TET-dependent DNA modifications.

However, there is abundant messenger RNA coding for HMCES inside normal, activated B lymphocytes, prompting the group to compare immune responses in HMCES-deficient versus normal adult B cells. Following antigen stimulation, normal B cells predictably “switch” their antibody repertoire from IgM to IgG antibodies. By contrast, lymphocytes from HMCES-deficient mice were less-efficient at making IgG antibodies, presumably because the CSR machinery that “recombines” DNA to convert IgM to other IgG isotypes is operational to a lesser extent without HMCES.

“In this study we used lymphocytes as a model system to identify a new role for HMCES in a lesser-known pathway of DNA double-strand-break repair,” says Shukla, referring to alternative end-joining. “But that pathway is not only active in immune cells. The kind of DNA double-stranded break repair we describe here likely occurs in response to DNA damage in any cell of the body.”

The research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Structural Genomics Consortium, among others.